Windows of opportunity: Solar cell with improved transparency

Tokyo - Roof-mounted solar panels are an increasingly common sight in many places. As a source of cheap, clean electricity, their advantages are obvious. However, most solar panels are opaque, and therefore cannot be placed over windows. Now, researchers at The University of Tokyo's Institute of Industrial Science (IIS) have made developments in the design of transparent solar materials.

Conventional solar cells contain silicon, which captures sunlight and converts its energy to electricity. The panels are dark, because silicon absorbs light across a wide spectrum of wavelengths, allowing very little to pass through. This makes them efficient generators, but opaque materials, even though the thin silicon layer is coated on glass. Therefore, the challenge is to create a material that absorbs enough light to produce power, yet still admits enough to remain transparent.

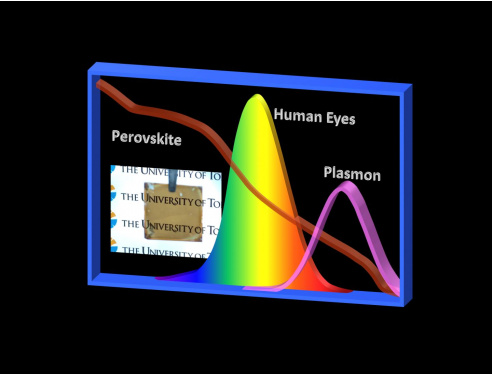

To tackle this, the IIS researchers exploited the properties of the human eye. As recently reported in Scientific Reports, they took account of the fact that, for visual purposes, not all colors are equal. In fact, the eye is much more sensitive to green light, in the middle of the spectrum, than red or blue. According to the rules of "human luminosity," a good supply of green light is the main priority for visibility. Their new material was therefore designed to mostly absorb red and blue light, while letting green through.

Instead of silicon, the cell is based on a material known as perovskite. A thin perovskite layer absorbs sunlight to generate an electric charge, which is transmitted to an electrode layer sandwiched between perovskite and a glass backing. Perovskites are particularly good at absorbing the less visually important blue light.

"Perovskites have been used for 'photovoltaic windows' before, as they are much more transparent than silicon," study co-author Gyu Min Kim explains. "However, there is a trade-off between using a thicker perovskite layer to produce more power, or a thinner layer to let more light through. This has limited their application up until now."

The researchers added another layer to their cell - nano-sized cubes of silver. Like perovskites, the use of silver nanocubes in solar cells is not new - they are already known to increase the efficiency of light-capturing. However, to focus on harvesting the red wavelengths, which are missed by the perovskite, the researchers boosted the nanocubes' effect by coupling them with the cell's other electrode layer, also made of silver. This encourages the "plasmonic antenna effect", which increases the cell's light absorption ability and, thereby, its efficiency.

"Like conventional solar cells, the plasmon resonance effect depends on absorbing light," co-author Tetsu Tatsuma says. "However, with the electrode-coupled plasmons, it's much easier to tune the wavelengths that are absorbed, simply by controlling the size of the nanocubes and the spacing between the nanocubes and the electrode. This allowed us to sensitize our cell to red light, making it complementary to the optical requirements of human vision."

After introducing the nanocubes, the overall light sensitivity was strengthened, which allowed the perovskite layer to be made much thinner. Despite the thin layer, an impressive power conversion efficiency of around 10% was retained. More importantly, the visual transparency was increased by 28%. This raises the hope of developing commercial solar cells that can be coated over windows, increasing the productivity of solar power.

The article, "Semi-transparent Perovskite Solar Cells Developed by Considering Human Luminosity Function," was published in Scientific Reports at DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-11193-1.

###

About Institute of Industrial Science (IIS), the University of Tokyo Institute of Industrial Science (IIS), the University of Tokyo is one of the largest university-attached research institutes in Japan. More than 120 research laboratories, each headed by a faculty member, comprise IIS, with more than 1,000 members including approximately 300 staff and 700 students actively engaged in education and research. Our activities cover almost all the areas of engineering disciplines. Since its foundation in 1949, IIS has worked to bridge the huge gaps that exist between academic disciplines and real-world applications.